On Saturday 26 October 2019, two groups of 6 people each led by 2 experienced trip leaders from the UNSWOC each went to Pipeline Canyon from Newnes campground (C on map). The groups left 1 hour apart, around 8 am and 9 am. They both gave their plan details and expected return time to the club’s executives staying at the campground. Other UNSWOC members were also doing the canyons nearby (Starlight, Devils Pinch and Firefly canyons).

The forecast was clear, with up to 20% chance of minor showers early in the morning and sunny for the rest of the day, with moderately strong winds peaking in the afternoon and evening. Both groups were carrying helmets, harnesses, abseiling devices, safety slings, prusik cords, ropes, anchor material, wetsuits, emergency blankets, dry warm clothes, first aid kits, maps and canyoning notes, navigation equipment, head torches, food and water. The second group was carrying a PLB. The four trip leaders hold Remote Area First Aid qualifications.

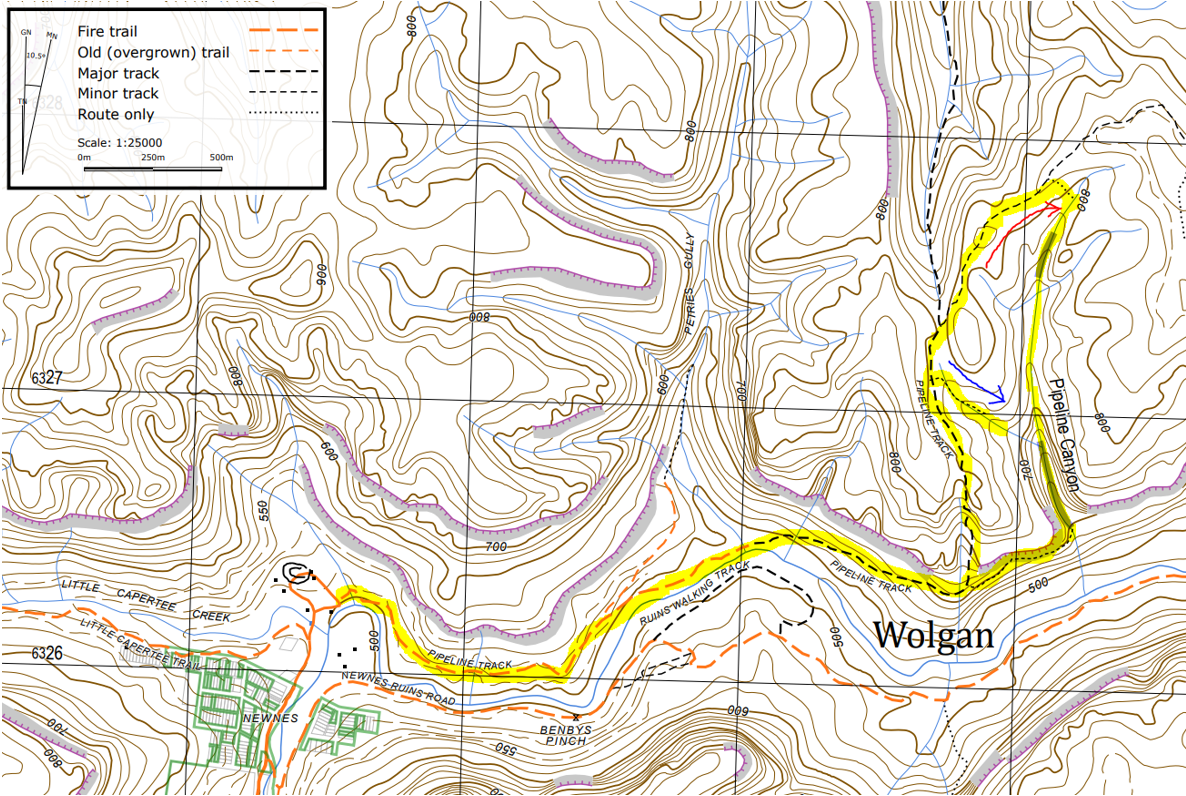

Pipeline features two sections of canyon (map 1), and both groups aimed to complete the whole canyon. During the hike in, the second group caught up with the first group before the RHS turn off that leads to the lower constriction. Both groups briefly stopped for a break and trip leaders discussed the directions each respective party would take. Since the second group was keen to do the upper constriction (red arrow) the trip leaders of the first group decided to take the shorter route entering the canyon in the lower constriction (blue arrow). This way there is less waiting around abseiling points, reducing the risk of hypothermia, and it gives both groups some distance to operate more efficiently.

Map 1. Map of the Wolgan canyons (https://ozultimate.com/canyoning/maps/wolgan_canyons.pdf)

The first group hiked towards the lower constriction, where there is a 5 m abseil / downclimb followed by a ~12 m abseil. They were looking for the anchor point at the second abseil (it didn’t seem to be located on any easily accessible or obvious spot) when they spotted an anchor made of red tape tied around a solid tree up to the left with a ring maillon on it (photo 1). The access to the anchor was a tricky steep downclimb with fallen branches and thick vegetation. One of the trip leaders asked the group to wait on safe ground and approached the downclimb to set up the abseil. The group lost sight of him while he was standing on a small slope ledge with loose dirt. He clipped his safety in, and the group heard a thud as he fell ~12m to the ground below. The group did not see the fall, which happened around 11.30-12 pm. They heard him calling but they could not make out the words.

Photo 1. Red webbing anchor for the abseil. Note that this photo is from 2015 and the anchor was lower this time.(https://www.subw.org.au/2015/10/17/newnes-weekend-starlight-and-pipeline-canyon/).

Taking control of the situation, the other trip leader asked the participants to stay calm and to stay where they were. Once he made sure they were safe, he set up a fixed line to safely approach the cliff and set up a new anchor point to abseil to the canyon floor on a second rope to check the casualty’s condition. The casualty was conscious but confused, trembling and scared. He was dry and the bleeding was minor but he had obvious injuries and pain. The trip leader trusted his instincts, provided remote area first aid as per training, kept the casualty warm with dry wetsuits and emergency blankets, and prusiked back up the fixed rope to send for help. He quickly asked for two volunteers to abseil down and stay with the casualty. They were given most of the food, water, emergency blankets and warm clothes, and they safely abseiled down to assist him. The casualty was laying down but kept trying to get up, which the two volunteers prevented to avoid a potential spinal injury.

The second UNSWOC group did not have any interaction with the incident because it occurred before the canyon proper (along the blue path). The second UNSWOC group moved through the canyon unaware that the first group had an accident.

The trip leader took the rest of the group back to the campground as quickly and safely as possible where he met some club executive’s and immediately called for help. They reached the police and emergency services. The trip leader didn’t assume that emergency services had the right plan and therefore urged the rescue coordinator to send in paramedics by foot ASAP, who ultimately reached him first, around 6-7 pm. He joined the paramedics on their way to the canyon. A helicopter flew over the canyon around 4-5 pm but could not access the casualty. Two more helicopters attempted to reach them during the evening, but the strong winds forced them to wait until Sunday morning. The two participants, the non-injured trip leader and a team of paramedics spent the night at the canyon, evacuating the casualty to higher ground above the abseil. It was an intense sleepless night with good cooperation and help by the UNSWOC members. During the night, strong pain-relief medication was provided and the casualty remained stable. The group was evacuated around 6-7 am on Sunday by helicopter. The injured trip leader is recovering in the hospital with the support of his family, friends, the club and the canyoning community. There is no head or spinal injury, but fractures on his humerus, femur and ribs. The prognosis for recovery looks promising. On behalf of the club, thanks to the paramedics and emergency personnel who did an outstanding job treating and evacuating the casualty.

- Most plausible explanation to the accident

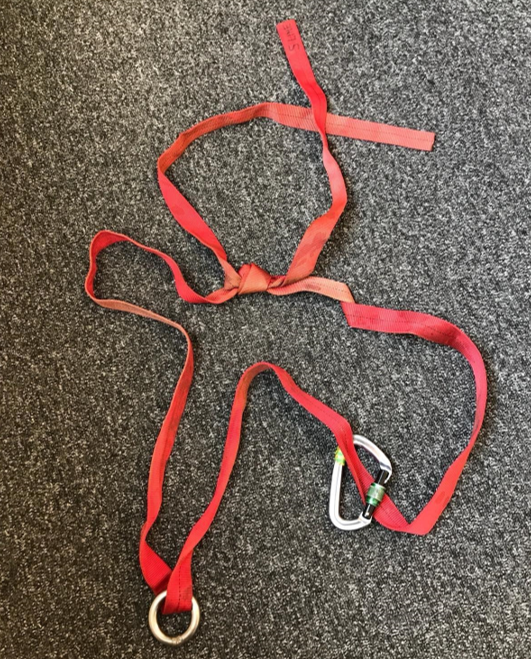

The casualty cannot remember how the fall happened but insisted he clipped his safety to the anchor. The red tape forming the anchor was found underneath the casualty’s body with his personal carabiner (labelled with green and yellow tape) clipped to it. Therefore, the anchor must have fallen with him, which likely implies he clipped to it. At the same time, the webbing, maillon and water knot are intact, eliminating the possibility of gear failure. The tree is also intact, eliminating the possibility of anchor-point failure.

Photo 2. Anchor retrieved by the paramedics from the casualty’s body. Water knot and maillon are intact. The carabiner belongs to the casualty (the connection from the carabiner to the harness has been removed in this photo).

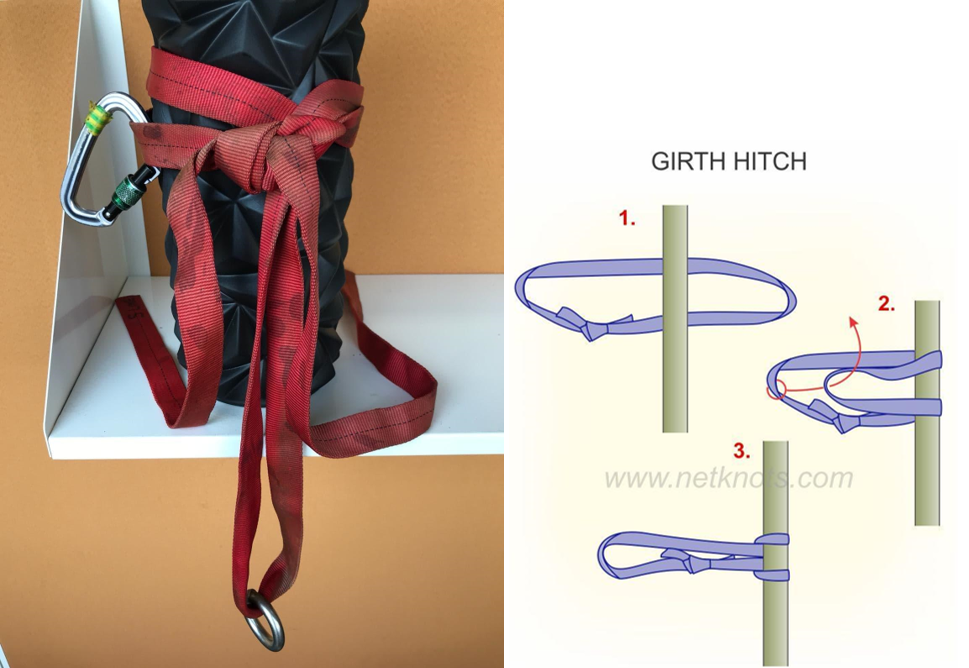

When looking at photo 1, it looks like the webbing was girth hitched to the tree. A girth hitch (photo 3) is a type of hitch that is valid as an anchor provided everything is clipped exclusively to the hanging loop / masterpoint (unlike other commonly used anchors such as cordelette, equalette, or quad; or the most common canyoning anchor, webbing looped around a tree several times and tied with a water knot). Clipping most canyoning anchors in the Blue Mountains from the side/back would not result in the anchor coming undone under weight. However, clipping a girth hitched anchor from the side/the back (for example, in an exposed approach, which is generally done from the back) would completely undo it when weighted.

With the collected testimonials and evidence, we think that the trip leader approached the tree from the side, and because it was an exposed approach, clipped his safety to the side of the anchor, as in photo 3 (instead of to the master point). When he fell, the girth hitch slid and came undone, resulting in a fall.

Photo 3. Girth hitched webbing and carabiner clipped on the side (https://www.netknots.com/rope_knots/girth-hitch).

- Avoiding the accident in the future

The most effective way to avoid anchor accidents is to test the anchor before putting your weight on it, as the trip leaders know. However, when in exposed or dangerous ledges (like this case), testing the anchor could be harder to do. From the UNSWOC, we recommend avoiding girth hitched anchors except for personal use (i.e. when you set up the anchor and take it with you after you finish, so you know it is a girth hitch). When setting up “permanent” anchors in a popular canyons for communal use, it is generally best practice to avoid girth hitches: they significantly reduce the strength of the webbing / sling, they increase tree-damage when compared to 2-3 loops of webbing, and they are only reliable if loaded on one end, unlike most other anchors.

The take home messages are (1) always check the type of anchor you are tying into, (2) always test the anchor before putting your weight on it, (3) use a safety line when approaching an exposed anchor, (4) reconsider tying girth hitches if better options are available, and (5) where possible always carry a PLB in a canyon to alert emergency services as soon as possible.

Cheers, Maria