Trip report by Elliott Vercoe (99%) and Brendan Conneely

Party of Elliott Vercoe, Cooper Walters and Brendan Conneely

Special thanks for David Mason's post and Tom Brennan's guide.

Preamble

‘One of the hardest, if not the hardest, of the canyons flowing into Kanangra Creek. It is a remote wilderness trip requiring advanced navigational and ropework skills. All of the party should have previous experience in Kanangra canyons. Travel light and fast.’

Carrabeanga falls as described by canyoning.org.au

Planning begins a few months earlier, when we need to understand our route and gear requirements. I made a post on the canyoning Facebook groups to find out if anyone had completed the canyon since the fires. I received many opinionated responses, only 1 of which was useful; from Michael Von Mengersen. He had completed it in 2022, and was aware of 1 other party who completed it in 2021. Both of them commented on the difficult state of anchors and trail.

The planning stage progressed by finding appropriate participants, and we settled on myself, Brendan, and Cooper. We would need a small group to move quickly, but still be able to carry a spare rope, and a team of 3 was perfect. Brendan and Cooper are both highly experienced and capable and it was great to have them on board.

We elected to bring 1 x 70 m, 1 x 60 m, and 1 x 45 m rope, allowing us all to rig independently. We decided to bring enough tape (35m) and mallions to replace 8 anchors - noting that we could always eat into the rope and our biners if we needed to.

Based on Tom Brennan’s guide, we planned for the trip to take 19 hours. However, we needed to be prepared for a bivy in case the trip blew out, so we packed a tarp and some overnight warm gear. We expected no rain, and a low of 10 C. We would be safe to bivy, but not comfortable. We brought enough food to last an extra half day.

We brought all our usual safety gear, including 2 Inreaches, a water filter, and handheld radios (waterproof walkie talkies). Wetsuits were not required in these water levels. We made the mistake of wearing our nice hiking clothes and they got completely torn to shreds.

The Trip

On Friday 17/11/23 we drove up to the mountains. After a pizza dinner from Rene’s, now Rustico???, we arrived at the Boyd River campground at approximately 2130. We set our alarms for 0400, aiming to leave the trailhead by 0430. It will be a long day without much sleep. Our gear is packed and ready to go asap. I rail 2 valium and am out like a light (maybe delete for a club post). Brendan: it's legal

We wake up and work through our morning routines. It is a 5 minute drive from the campground to the startpoint at King Pin fire trail. It’s an unusual coincidence that Brendan’s nickname is also King Pin. We start walking at 0458, about 45 minutes before dawn. The start of the trip is just a fire trail and can be easily done in the dark.

We reach the junction of the fire trail and the Mt Paralyser track. There is a faint trail leaving the road, but it quickly disappears to an open grassy plateau, populated by sparse sections of dense regrowth. We avoid the regrowth and follow the ridgeline until the turnoff point to Burra Gunama Hill. This is not a popular route.

We leave the Mt Paralyser Track and start heading towards Burra Gunama Hill. The ground is easy here, without many dense sections, and we make good time. Once reaching the hill, we follow the spur into the creek directly above the start of the falls proper.

We reach the start of the descent at about 0800. Unpacking our gear lets us have a snack and a red bull, and rack up for the first abseil. There is hardly any water in the creek, much less than we saw in photos from previous trip reports, which is consistent with our expectations.

The second abseil consisted of a rope that had been melted by a fire, backed up by a slightly munted piece of tape, with a rusty mallion. The tape looked fine and the mallion would hold, so we backed it up with a sling and sent Cooper and Brendan down to weight it, and then I brought the sling down at the end once we knew it held. The anchor was a remnant from before the fires, and showed that the fire had even damaged this tree far out on a rock ledge. This one had survived, but many more had been burned away.

The guide suggested that there was an anchor to the left of the falls, however we were unable to find it. Either the anchor has gone, or the whole tree has been destroyed. Cooper set a new anchor, cutting the tape to size and looping in a new mallion.

After abseil 3, we wander around the ledges looking for abseil 4, or alternatively a way to scramble down. There are a series of rock ledges, covered in foliage debris and scree piles. Cooper manages to get down, but Brendan and I decide to throw the rope around a few trees to abseil and avoid any risk. This takes a bit of time. At this point we've realised the canyon topo is mostly useless and we'll need to make our own route.

Eventually in the distance we see an old rope wrapped around a tree to true right of the waterfall, giving us a target to head towards. We set up one more anchor to rap down to it, and scramble across some wet ledges to reach it. Cooper checks and rebuilds it, and rigs the rope to head down into the main falls.

By this point the rock fall has become so bad that we need to adopt some serious policies to avoid knocking rocks onto the active abseiler. We end up finding comfortable positions, sending 1 person down the abseil, and then freezing in place until they are off rope and out of the fall line. Then the next person goes, while the top person remains frozen. Simply walking around would dislodge scree and gravel and was a major hazard to the person below. This made the next few abseils extremely slow.

The guidebooks said to abseil about 15 m to a small ledge and rig a new rope to allow traversing to the true right. I abseiled down about 15 m where I reached a tiny flake splitting off the wall, next to a gum tree growing out of the cliff. The tree was about the diameter of a big hug, and had a nice gap I could pass tape through. Surely this must be the anchor as described, but there was no tat to be seen, and it couldn’t have been damaged by the fires. The flake itself looked like it would break apart if I kicked it, and it was covered in dinner plate size loose rocks. This loose rock did not make for a good stance.

Instead of requiring multiple people to stand on this messy flake, I communicated via the radio that Cooper and Brendan should come down and transfer abseil ropes from a lower ledge, without coming near the anchor. I weighted the gum tree as Brendan and Cooper passed below me and found the next anchor.

After the 60 m abseil on the main falls, we couldn’t work out a safe way down the next scramble, so Cooper rigged a new anchor around a large boulder to bring us down into the canyon proper. The terrifying crack of rockfall naturally ricocheting down the falls and sharp boom crack of clearing choss (video)

The canyon proper was interesting and narrow, but there were trees on the sides which had at some point been used for anchors. We continued down, happy to be out of the sun, repairing damaged anchors and improvising our way along.

We reached the long sloped falls, which was a pleasant low angle abseil taking us down into a shallow pool. The low flow meant that we stayed dry. It is possible to do this in 1 pitch with a 70 m and a 60 m rope joined together.

Michael had advised us that their 2022 expedition lost a bag into the canyon at some point, and to keep an eye out for it, as he had a keg with electronics and car keys that should be still good to use. We came across bits of the bag strewn across the creek; first a rain jacket, then a damaged rope, and then finally the white canyon keg lodged under a rock. The lid had jammed tight so I smashed it open and was greeted by the worst smell I’ve ever experienced. Inside the keg was an old chicken roll that had fermented into a living goo and covered the entire keg in mould. I coughed and screwed the lid back on.

Brendan shows up and we decide to cover our faces with our buffs and have a look. We pour out the contents, but everything is covered in a layer of this biohazard mould. Picking through the internals with sticks, we find some keys and some electronics, but they are covered in slime, and we decide there’s no way we can safely carry these out. We pack them up as best we can and move on.

We reached Kanangra Creek at 6 pm. It’s time for dinner and I eat my wraps and share another Red Bull (the others did not pack an appropriate amount of caffeine). The stream was flowing and clear and we were able to filter water and refill our capacity.

It was starting to get dark, and there would be no other bivy options until reaching the top of Cyclops Ridge. At 1000 m vertical with no trail, I expected it would take at least 4 hours to rech the top. This proved to be an underestimate.

Full of taurine and carbs, we agreed that we did not need to bivy, and could reassess our options once reaching the top of the climb. We continued down the river, and found the spur leading out of the river before dusk. It was important to get as much of the lower climb out of the way while we still had light.

The climb proceeds out of the river along a wide buttress, and we take the line of least resistance as much as possible. The regrowth becomes thicker and thicker, until we are mostly crawling on a layer of leaves, grasping and pulling on chunks of plants to make vertical headway. At random points the regrowth canopy collapses beneath us as we fall waist deep into plants and need to extract ourselves - a tiring task after 14 hours of moving.

However, the route is quite safe and we are glad to feel it. Compared to Manslaughter ridge (the Kanangra / Kalang exit) this way is much safer with significantly less rock fall and loose ground. But it is physically harder, slower, and contains twice as much elevation gain.

Once it has become proper dark, the buttress became more of a knife blade ridge. This made navigation much easier, as we could just follow the highest possible line, and the route would drop off to either side. The sharpness of the ridge meant that there was less vegetation and more rock scrambling, which let us make better time.

On our way up through some shrubs, I hear Brendan call ‘Rock!!!’ and I see a large mass start hurtling towards me. I was shocked for a second, particularly because I was above Brendan on the ridge. Once we narrowed our torches on the object, we saw that it was actually a huge wombat charging uphill. He barreled past me and disappeared into the bushes. We inferred that he and his compatriots must have been responsible for many of the crushed plants that we saw that would occasionally form a path of least resistance.

We reach the top of the climb around 2330. Brendan and I continue a bit higher towards the GPX route marked as ‘Mt Paralyser Track’, praying for a beautiful highway, but there is nothing at all there. Cooper is salty that we did more elevation than we needed to.

At this point Brendan and I are out of water, but Cooper remarks that he has an extra 2 L, saving the day for us all.

The next slog from the top of the climb to the car would involve about 4 km of ridge traversing through dense bush, at night, while exhausted, and then about another 4 km of repeating the trail from start of the day. At this point in the trip I am nonverbal, Brendan is in all sorts of miscellaneous pain, and Cooper is perky and talkative. Cooper takes the navigation reins and leads us through the dark, despite our constant complaining and being unsure of whether to stop and bivy. At one point we sit down to rest for 2 minutes and Brendan falls completely asleep, lying on his side with his pack still on.

By now I have the onset of trench foot from walking in wet shoes for a full day. We are each fighting our own battles, and unsure whether it's worth continuing for the night or bivying until sunrise. The temperature is good, there's no rain, and the various shrubs are super comfortable to lie on. When making the decision, we collectively thought back to the scene from Troy, where the small boy tells Achilles that he would be scared to fight Boagrius, and Achilles responds ‘And that is why no one will remember your name’. So we kept on walking.

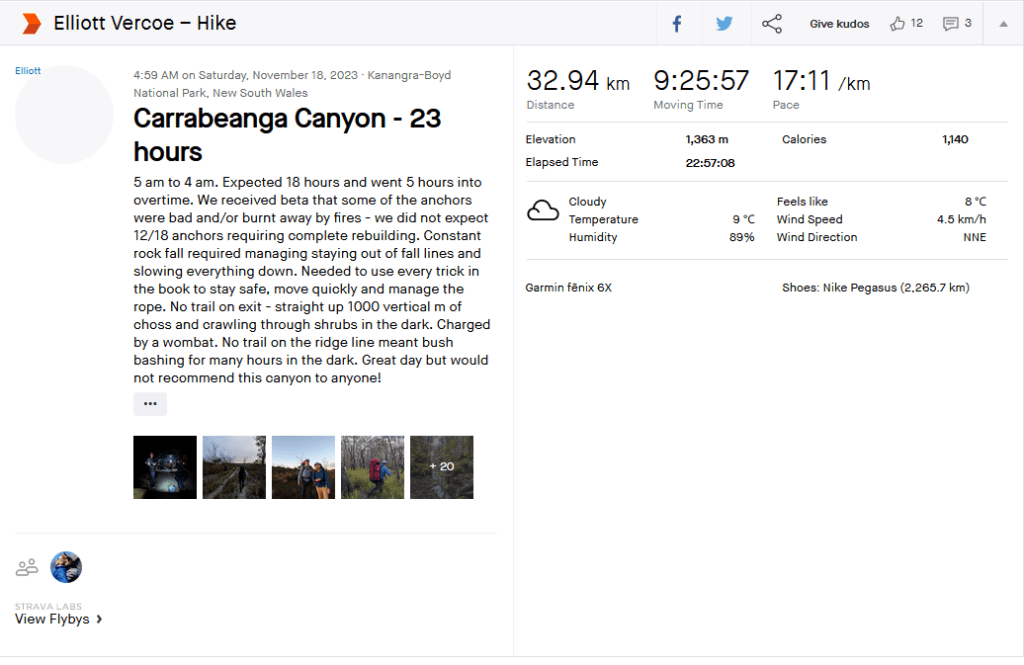

With a sigh of relief, we made it back to ground we had previously covered, and then it was only a few more hours to the fire trail, then to the car. We walked that fire trail silently counting down the distance remaining on the GPS. Finally we see the car, we quietly load our gear into the boot, drive the 5 minutes to the campground and pass out in our tents. Finished in 23 hours, just under a single day.

Conclusion

The canyon itself was incredibly dangerous for the wrong reasons and I would not recommend this trip to anyone. The rock fall was such a miserable and severe hazard to manage and spending too much time in Carrabeanga falls proper is just asking for trouble. I have spent a lot of time in the mid-high Himalayas, traversing loose and crumbling glacier scree for days, and the rock fall hazard in Carrabeanga was much more dangerous. We all had weird dreams of anchors and rock fall and bush bashing, a hallmark of a highly traumatic experience.

If looking for a similar endurance challenge, it would be far better to link up a bunch of other canyons; maybe Kalang x Kanangra x Danae, or something like 10 Wollangambe canyons in a row. For a remote wilderness challenge, a section of the 3 peaks would be better.

Ultimately we are all glad we did this trip but we would never do it again.

Brendan’s thoughts

Carrabeanga has always been a longstanding goal of mine. When I first commenced canyoning and got a hold of the Jamison 'Canyon's Near Sydney' book, I would spend nights reading of the large and intimidating trips in Kanangra - Carrabeanga being one of the most wild. The accident reports of the Newcastle University fatality in Carrabeanga Canyon have always been at the back of my mind, and meant that serious preparation would be needed. Cooper, Elliott and I all had a healthy respect for this trip, and the rockfall risk we encountered validated these real dangers. Achieveing this goal required years of skills development, fitness and training. The trip was a 'wild' trip, similar to my experience attempting (and failing) the 'Three Peaks Challenge' this year. I was pushed close to my limits, and from midnight onwards I felt close to rock bottom, due to my workload prior to the trip. I could have laid in the dirt and slept comfortably (and I did). It was a learning lesson regarding pre-trip rest, the impact of sleep on your energy reserves, and how work schedules affect your performance for these extreme endurance events.

Strategy wise, completing the ridge up to Mt Cyclops at night was a good decision, allowing us to avoid the extreme heat that we would have otherwise experienced during the day (for the full 6 hour climb). Making a bivy camp near Mt Cyclops would have improved our navigation troubles caused by the thickly vegetated and less 'distinct' ridge line that took several hours to cross. The moon had set so there was no background light to distinguish the contours along the ridge, impeding our navigation. I was pretty much a zombie by this point - thanks Cooper for leading the charge. I think the entire trip exposed us all to new challenges, posed by a fire damaged landscape that will continue changing for decades.

With enough time, the memories of rockfall and the waist deep vines on Cyclops spur will pass, and perhaps I'll make another journey into Carrabeanga Falls. Until then, I'm happy to have survived, found some new limits, and spent an adventure with great company. While I would not recommend this canyon due to its inherent risks, I believe it's important for each group to assess these on their own. While not the most breathtaking in terms of scenery, this canyon offers a unique sense of adventure, particularly as it hasn't been explored by many recently. This trip is something you must plan for, train and execute with a small experienced party. Be prepared for significant rockfall hazards, and note that the dense vegetation and damage from past fires can transform an already lengthy expedition into an extremely challenging endeavor. Beware!

Abseil List

These are the abseils we performed corresponding to the abseils listed in the canyoning.org.au quick reference. The guide and references were helpful for the main abseils down the face of the waterfall, but otherwise appear to have become irrelevant with changes to the canyon forestry.

| Topo | Description |

| 2 | RL after scrambling down the first waterfall |

| 3 | RL after scrambling around some bushes |

| Not sure what was meant to happen here. We ultimately want to be heading to RR. The next 2 abseils can be scrambled around to get to the first major anchor in the main falls. | |

| ??? | Off a random tree RR |

| ??? | Off a random tree RR |

| ??? | Proper anchor again; a rope slung around a large tree RR. Descend this then traverse and scramble up to the next anchor around a tree. Not marked on reference. |

| 5 | This is marked in the canyon reference as being a 15 m abseil, towards abseilers left, to a ledge. There is a messy loose flake about 15 m down, where we built an anchor on a solid gum. This sucked and couldn’t accommodate more than 1 person, and was just a pile of loose choss hanging off a cliff |

| 6 | Described as 42 m to a bush ledge. Accurate: do not descend past the bush ledge or you need to scramble back up to find the next anchor to abseiler’s left |

| 7 | Good logical anchor from tree for 60 m abseil |

| ??? | The scramble down into the canyon slot was messy and wet so we slung a boulder and abseiled down |

| None of the next few abseils correspond with anything we found in the topo or were described in the guide | |

| ??? | RR after scramble across loose bush slope |

| ??? | Honestly there were a bunch of random abseils here until we got to the big waterfall. Make something work. Some pools here so can be tricky to stay dry |

| 14 | 65 m long sloping waterfall, lots of fun |

| 15 | 42 m down a beautiful plant covered waterfall |

| ??? | Again, a few more random abseils not listed. Nothing particularly long. |

Thats all folks...,